My previous graphic essay on the global housing crisis used San Francisco, New York, and Berlin as case studies to visualize the loss of personal belonging and the destruction of communal memory. My friends liked it, but some suggested that I should have included Shanghai, the city of my birth.

The opportunity conveniently presented itself when I was invited to review a book set in my childhood neighborhood. As I followed the author’s account of that place, my thoughts and feelings roiled.

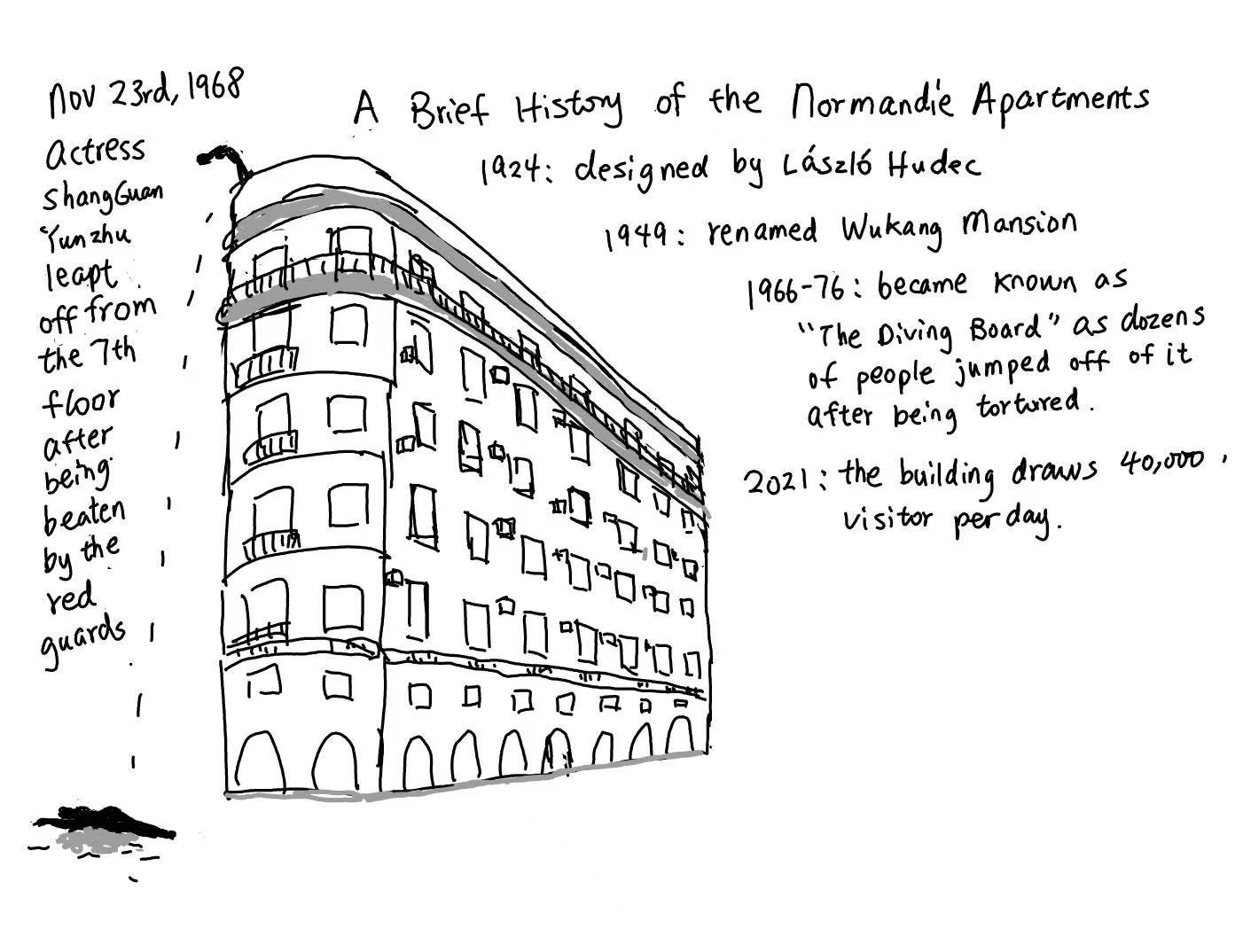

So here it is—last but not least—a dirge to that special corner of the Far East: although officially not a free-market economy and surely with some distinctive Chinese characteristics—its fate is still one of erasure and displacement much like the rest of the world. In this global age, the “end of history” has arrived, but fully on the other end.

AN EXCERPT:

These days, the French Concession is epitomized by trendy streets like Anfu Lu and Yuyuan Lu. These names, however, mean very different things to me: I was born and raised on Anfu Lu, our family of four squeezed into two partitioned rooms in a Xincun-style lane house. On weekends, we would visit our granduncle’s villa on Yuyuan Lu—by then already packed with a dozen more families. In those days, the city was cloistered and gray, but also slow and intimate.

Next time I returned, our home on Anfu Lu was demolished. It was later rumored that the development plan was instigated by one of Hong Kong’s wealthiest tycoons. With the state’s blessing, the seat of my childhood turned into high-end storefronts and luxury towers. Most of the old residents dispersed, relocated to faraway places they scarcely knew, living in new modern units isolated away from each other. Nowadays, as I stroll those same streets, greeted by fancy window displays and young women taking selfies, I couldn’t help but wish for something different. What if provocative art were commissioned to commemorate all those who were purged or displaced—much like the German Stolpersteine, small cobblestones inscribed with the names of Holocaust victims and installed in front of the houses of deportation. What if the old houses were not demolished for tourism and consumption, but remained as living spaces for ordinary citizens—where kids like me could play outside and neighbors chatted after work? Thanks to Fedder—those possibilities and remembrances—swept aside by the merciless march forged by power and capital—would endure on the page.

Eileen Chang, that brilliant native chronicler of Shanghai, once wrote this about modernity:

The locomotive of the Age roars forward relentlessly. We sit inside, passing perhaps just a few familiar streets, yet amidst the blazing flames of destruction, even they appear terrifying and unsettling.

Terrifying and unsettling as the motion is, words and fiction have what it takes to slow it down. The pause they effect—however slight—allows us to gaze, so that amidst the trembling ruins, florets of empathy and compassion could unfurl and blossom.